My Medicine Notes

Table of Contents

- Aesthetics

- Allergy/Immunology

- Behavioral Medicine

- 5A's

- 5 A's behavior change model edit

- Anger and Emotions

- Anxiety Traps

- BATHE Technique

- CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) Technique edit

- CBT Tools

- CBT Videos edit

- Child psych

- Coping strategies to teach patients

- Divorce edit

- Empathy

- Exposure Therapy for OCD: Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP)

- Gratitude

- HRV and stress edit 2024

- Managing anger and disappointment

- Military Psychiatry

- Mindfulness

- Motivational Interviewing (MI)

- Online Therapy Services edit

- Opposite Action

- PLISSIT Technique

- Shared decision making

- Stages of Change

- Stop Catastrophizing

- Study: Anger is eliminated with the disposal of a paper written because of provocation

- Study: Bypassing versus correcting misinformation: Efficacy and fundamental processes

- Study: Gratitude and Loneliness: Enhancing Health and Well-Being in Older Adults

- Study: How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing

- Study: Latent Diversity in Human Concepts (Language hinders discourse)

- Study: The Relationship Between Gratitude and Loneliness: The Potential Benefits of Gratitude for Promoting Social Bonds

- Study: The utility of prolonged respiratory exhalation for reducing physiological and psychological arousal in non-threatening and threatening situations

- Study: Gratitude and Mortality Among Older US Female Nurses

- Study: The Effort Paradox: Effort Is Both Costly and Valued

- Study: Comparing the Effects of Square, 4-7-8, and 6 Breaths-per-Minute Breathing Conditions on Heart Rate Variability, CO2 Levels, and Mood

- Breathing 4-7-8 - Study: Benefits from one session of deep and slow breathing on vagal tone and anxiety in young and older adults

- Calculators

- Cardiology

- 4 Factors of O2 Consumption For Heart Work

- 5 Most Common Causes Of Sudden Cardiac Death In Young Athletes

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

- ACC Tools

- AHA's Simple Seven

- Arrhythmias

- ASCVD

- Basic Life Support (BLS)

- Cardiac Clearance for Surgery

- Cardiac Medications

- Cardiology Differential

- Cardiovascular Fitness (CRF)

- Carotid Artery Stenosis

- Carotid US Screening

- Chest pain

- Common triggers for AF edit

- Compression Socks edit

- Coronary Artery Calcium Score

- Coronary Artery Disease

- Costochondritis and Tietze's syndrome edit

- CVA

- D-Dimer increased plasma values

- Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Chest Wall Conditions

- Patient Thrombotic Risk Definitions

- Deep Venous Thrombosis

- Eating Eggs Is Not Associated with Cardiovascular Disease

- EKG

- Heart Failure

- Hyperlipidemia

- Hypertension

- Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

- Lymphadenopathy

- Lymphedema

- Max/Target Heart Rate

- Metabolic Equivalents (METS)

- Murmurs

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- OTC Blood Pressure Cuffs

- Patient Messaging: Venous Insufficiency edit

- Peripheral Arterial Disease

- Post MI Medications

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)

- Prognostic Significance of Between-Arm Blood Pressure Differences edit

- Reduce Leg Swelling edit

- Study: Long-Term Effect of Salt Substitution for Cardiovascular Outcomes

- Study: Rate Control With Beta-blockers Versus Calcium Channel Blockers in the Emergency Setting: Predictors of Medication Class Choice and Associated Hospitalization

- Study: Replacing salt with low-sodium salt substitutes (LSSS) for cardiovascular health in adults, children and pregnant women edit

- Study: Use of Cardiac Troponin Testing in the Outpatient Setting edit

- Troponin Increased Plasma Values

- Prevention of Thromboembolism Guidelines for Atrial Fibrillation edit

- Study: Assessment of ASCVD Risk in Primary Prevention edit

- Dental

- Study: The Prophylactic Extraction of Third Molars: A Public Health Hazard

- Study: Imaging modalities to inform the detection and diagnosis of early caries

- Study: Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients

- Fluoride Supplementation in Community Water Question

- Dental Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Study: Common Oral Conditions A Review

- Dermatology

- 9 tips to help prevent derm biopsy mistakes

- Acne

- Acne Rosacea

- Alopecia (Hair Loss)

- Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

- Bed Bugs

- Best treatment for mild-mod acne vulgaris

- Burns

- Carcinomas (Basal Cell and Cutaneous Squamous Cell)

- Cellulite edit

- Chronic Urticaria

- Common Benign Skin Tumors edit

- Dermatology Procedures

- Dermoscopy

- Folliculitis

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Hyperpigmentation

- Infections, Insect bites, and Stings

- Ingrown Nail

- Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars

- Lice Treatment

- Medications

- Melanoma

- Milaria (Heat Rash) edit

- Molluscum

- Nail Abnormalities

- Nevus

- Nonscarring Hair Loss

- OCP and Acne

- Onychomycosis

- Paronychia

- Perioral dermatitis

- Pigmentation Disorders

- Pruritis edit

- Psoriasis

- Seborrheic Dermatitis

- Sebacceous Cysts

- Skin Protection

- Skin Type Classification

- Terminology

- Tinea Management Pitfalls

- Topical Corticosteroids

- Xanthoma edit

- Wood's Light edit

- Drugs/Medications/Supplements

- Adverse Effects: 10 Most Commonly Filled Prescription Medications in 2019

- Adverse Effects: Opioids

- Alcohol Use

- Antidepressants and Sexual Function

- Antidepressants and Weight edit

- Ashwagandha

- Auvelity Notes

- Benzodiazepines edit

- Bupropion

- Caffeine

- CAM with evidence

- Cannabis/Marijuana

- Chocolate

- Chronic use of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors:

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

- Contraception

- Controlled medications

- Controlled Medications (Schedule drugs) FL

- Corticosteroids

- Coumadin (Warfarin) Dosing/Management

- Creatine Supplementation

- diclofenac

- Dispose of medications

- Folic Acid Supplementation Lowers Suicide Events

- GLP-1 Agonists

- Study: Tirzepatide for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Obesity

- Study: Associations of semaglutide with incidence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder in real-world population

- Study: Semaglutide and Tirzepatide reduce alcohol consumption in individuals with obesity

- Study: Exenatide once weekly for alcohol use disorder investigated in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial

- Study: Repurposing Semaglutide and Liraglutide for Alcohol Use Disorder

- Glucocorticoid Equivalents

- Iron (Fe) Supplementation

- Ketamine for Depression

- Medication Prescription Helps

- Medication Resources

- Medication thoughts relating to homeless persons/street

- Medicine Reconciliation and Medical Error

- Metformin Tips

- Methotrexate (MTX)

- Metoprolol

- Muscle Relaxers edit

- My (Formulary) Goto/Easy medication choices

- My Medication Rules

- Naltrexone: Low Dose Naltrexone

- Nitrofurantoin (Macrobid vs Macrodantin)

- OTC Symptom Management edit

- oxymetazoline (Afrin)

- Pharmacies: Canadian Pharmacies

- Pharmacies: Compounding Pharmacies edit

- Pharmacies: On-line Discount Pharmacies

- Pharmacies: Publix Save on Medications

- Placebo Effects

- Pregnancy

- Probiotics

- Procedural Sedation and Analgesia

- Protocol for radiocontrast in high-risk patients (Contrast Allergy)

- Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed)

- Quviviq

- Sick call med list

- Stimulants

- Top 100 Most Prescribed Drugs in the US (2023 Data)

- Topical Medications

- Topical Retinoids edit

- Vicks 44

- Vitamins, Minerals, and Supplements

- Study: Multivitamin Use and Mortality Risk in 3 Prospective US Cohorts

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)

- B complex

- Calcium

- Green tea (Camellia sinensis)

- Herbs

- Magnessium

- Minerals

- Omega-3

- On Supplements

- Vitamin B12 /Vit B12 Deficiency

- Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold

- Vitamin D

- Fish Oil:

- Study: Testosterone administration reduces lying in men

- Study: Therapeutic Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: A Review edit

- CGM Standard Written Order edit

- DME Suppliers edit

- Study: Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration

- Study: The loss of efficacy of fluoxetine in pediatric depression: explanations, lack of acknowledgment, and implications for other treatments

- Endocrine

- Cortisol Levels are likely Good

- Cushing Syndrome

- Diabetes

- Cutaneous Signs

- Diabetes self-management and support (DSME/S)

- DKA and HHS Management

- DM visit EBM

- General Notes

- HbA1C and Estimated Average Glucose Level

- Iatrogenic Hypoglycemia

- Insulin

- Diabetic Neuropathy

- Management Plan for Type 2

- Oral medications

- Self-monitoring

- Special tests to classify DM

- Weight loss in pts with DM 2

- Sulfonylureas (SU)

- Estradiol (Vaginal) edit

- Glucocorticoid-Induced Adrenal Insufficiency edit

- Hormone Replacement Therapy edit

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring

- Pre-Diabetes

- Testosterone

- Secondary hypogonadism

- Endocrine Guidelines:

- How To Self Inject Testosterone

- Normal Testosterone Levels by Age (20-45) edit

- Other Medications

- Study: Association of specific symptoms and metabolic risks with serum testosterone in older men

- Testosterone Levels by Age edit

- Testosterone Order edit

- Who to treat

- Thyroid

- Diabetes Type 1 (T1D)

- ENT (Otolaryngology)

- Allergic rhinitis

- Allergy tips

- Anosmia

- Aphthous Stomatitis (Canker Sores)

- Cerumen

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis

- Hoarseness

- Motion Sickness/Vestibular Nause

- Neti Pots

- Olfactory Training edit

- Otitis Externa

- Patient Messaging: Protect ears during scuba diving

- Pulsatile Tinnitus

- Rhinitis

- Sinusitis

- Sore throat

- Spots on Tongue edit

- Temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome (TMJ) Pain edit

- Tinnitis

- Gastroenterology

- Albumin/Globulin

- Antiemetics Selection

- Barrett Esophagus

- Bowel cleansing

- Bowel Medicines

- Celiac Sprue/Gluten Insensitivity edit

- Liver Cirrhosis

- Patient Messaging: Liver Cirrhosis

- Diagnosis and Initial Assessment

- Treating the Underlying Cause

- Lifestyle Modifications and Nutrition

- Immunizations and Medication Safety

- Surveillance

- Management of Complications

- Symptom Management

- Care Coordination and Transplant Evaluation

- References

- Ascites treatment

- Acute variceal hemorrhage

- Colonoscopy

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Dietary Fats

- Diverticulitis

- Dyspepsia

- Elevated Liver Transaminase Levels

- Flatus and Bloating

- Flatus control

- Food Allergies

- Food-Borne Illnesses edit

- Gall bladder Diet edit

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastroparesis

- Hemorrhoids

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- IBS Diagnosis (Rome IV)

- Diagnostic Criteria

- Evaluation

- Alarm Features Suggesting the Possible Need for Further Testing

- IBS with Constipation:

- IBS with Diarrhea:

- Mixed IBS:

- IBS Treatment/Management:

- First-Line Management of IBS and Other Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

- Diet: Avoid Gas producing foods

- Diet: General IBS Dietary Ideas

- Diet: Low FODMAP Diet

- Diet: FODMAP Food Reference

- FoodMarble - MedAIRE and MedAIRE2 edit

- Jaundice

- MicrosCopic (Lymphocytic And Collagenous) Colitis

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD Score) edit

- NAFLD

- Pancreatitis - Chronic

- Rectal Prolapse

- SIBO

- Transaminases

- Gallstone Diet Patient Instructions

- Low FODMAP Apps

- Geriatrics

- Constipation in Elderly

- Delirium

- Dementia

- Driving safety edit

- End of Life Care

- Falls

- Frailty

- Hospice

- Indications for Mental Health Referral

- Early Signs of Dementia vs Normal Cognitive Changes Related to Aging

- Insomnia in Geriatrics

- Medications in Geriatrics

- Mobility Assist Devices

- One-legged Stand

- Osteoporosis

- Osteoporosis

- Preoperative Evaluation and Frailty Assessment in Older Patients edit

- Study: Abdominal fat depots are related to lower cognitive functioning and brain volumes in middle-aged males at high Alzheimer's risk

- Study: Hypertension linked to Alzheimer's disease via stroke: Mendelian randomization

- Study: Hypertension and Alzheimer's disease pathology at autopsy: A systematic review

- Study: Blood Pressure, Antihypertensive Use, and Late-Life Alzheimer and Non-Alzheimer Dementia Risk: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis

- Study: Heavy resistance training at retirement age induces 4-year lasting beneficial effects in muscle strength: a long-term follow-up of an RCT

- Study: Galantamine for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment edit

- Study: Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging

- Study: What Is the Association Between Music-Related Leisure Activities and Dementia Risk? A Cohort Study

- Study: Topological turning points across the human lifespan edit

- Hematology/Oncology

- Abnormal bleeding or bruising

- Anemia

- CBC with differential

- False A1c Readings

- Gastric Cancer

- Hemoglobin C Disease edit

- Iron (Fe) Deficiency Anemia

- Lung Cancer Screening

- Lymphadenopathy Causes

- Meat Consumption and Cancer edit

- Unprocessed Red Meat and Processed Meat Consumption: Dietary Guideline Recommendations From the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) Consortium edit

- Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies edit

- Lifetime Risk of Developing or Dying From Cancer

- Multiple Myeloma

- Neutropenia

- Peripheral Lymphadenopathy (LAP) edit

- Polycythemia Vera

- Prostate Cancer Screening

- Study: Projected Lifetime Cancer Risks From Current Computed Tomography Imaging

- Study: The Association Between Smartphone Use and Breast Cancer Risk Among Taiwanese Women: A Case-Control Study edit

- Infectious Disease

- Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis (ABRS)

- Acute Gastroenteritis

- Acute Respiratory Tract Infections

- CDC Outpatient Antibiotic Recommendations edit

- CDC Treatment for Common Illnesses edit

- Colds vs Flu

- Common Cold EBM

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

- FLCCC - Prevention Protocol (COVID-19)

- FLCCC - Early Outpatient Treatment Protocol (COVID-19)

- COVID Risk factors for Death and Hospitalization (Medicare Population)

- COVID Ideas/Opinions

- COVID Treatments

- COVID Vaccines

- EUA

- Masks

- Random Stats Stuff

- Outpatient COVID-19 Management

- Testing Guidance for COVID-19 - Jan 2022 edit

- Mortality Stuff

- Vaccine Stuff

- Cutaneous Larva Migrans

- Dog and Cat Bites

- FL Prevent Mosquito's edit

- Foodborne Pathogens

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- HIV

- H. pylori

- Immunizations and Vaccines

- Influenza

- Influenza vs Common cold edit

- Insect Repellents

- Insects

- Monkeypox

- Otitis Externa

- Paronychia Home Care Instructions

- Pet Related Diseases

- Pharyngitis

- Pneumonia (Community Acquired)

- Postexposure Doxycycline to Prevent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections edit

- Post Infectious Cough

- Procalcitonin

- Red flags in a child with diarrhea

- Scabies

- Sepsis

- Tick Borne Diseases

- Traveler's Diarrhea

- Tropical Diseases from geographic areas

- Uncomplicated Cystitis (UTI)

- Waterborne Illnesses

- Wounds

- Study: Upper Respiratory Tract Infection edit

- Misc Medicine

- 2024 Anchor Imaging edit

- 25 Most Common Diagnoses

- AAFP Online Help edit

- Advanced Directives

- Art and Philosophy of Medicine

- Benefits of a dog edit

- Biostatistics

- Key Concepts When Looking At Research Studies

- PICOTS for the Trial:

- Cancer Screening Definitions

- Example of Interpreting A Study Results (Just a 1% difference)

- Random Statistics in Medicine edit

- What did 95 Percent effective mean (COVID) edit

- Biostat Terms

- Shared Decision Making And Using Numbers

- Safety Statistics

- Life Expectancy

- p values

- Study: The (Mis)Reporting Of Statistical Results In Psychology Journals

- Books For Patients To Read From Library

- Chloride Levels

- Coding

- DCF Contact edit 2024

- Disability Tools edit

- Executive Physical Exam edit

- Family Medicine and AAFP

- Favorite Patient Quotes

- Federal Poverty Guidelines For 2023

- First Aid Kits edit 2025

- FL Emergency Kit Components edit

- Florida Things that Bite edit

- Fun Medical Definitions

- Grandmother's Rules of Life edit

- Health Insurance Analysis (Opinionated)

- Homeless Resources

- HSA Is OK With DPC Edit

- Human Trafficking edit

- Informed Consent 2025

- Insurance Notes edit

- Insurance Stuff

- Legal Stuff

- Lifestyle Medicine

- List of Physician Side Hustles

- Local Women's Shelter Resources

- Low Income Resources Central Florida edit

- Malpractice Risk Knowledge

- Medical Emergency Codes

- Medicare Advantage vs Medigap (supplemental) edit

- Medicine Tool Kit

- Physiology (Misc)

- Pt quotes edit

- Readmission

- Sample Letter From Health Care Provider: For Any Needed Accommodation

- Scope of Practice (For NP/PA) Expansion Talking Points (Opposition)

- Service Animals

- Social Media in Healthcare

- Study: Examining gender-specific mental health risks after gender-affirming surgery: a national database study

- Study: Racial and Ethnic Differences in Homework Time among U.S. Teens

- Teaching

- Tech Stuff

- Travel Medicine

- VA Nexus Letters

- Wellness Visits (Medicare)

- Study: Commercial Insurers Paid More For Procedures At Hospital Outpatient Departments Than At Ambulatory Surgical Centers

- Lab References

- Musculoskeletal/Orthopedics

- 52 WALKING FUN FACTS edit

- 90 Second MSK Sceening

- Acute Pain from Non-Low Back Musculoskeletal Injuries

- Ankle Pain

- Benefits of exercise

- Bone Stress Injury Prediction Rule

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

- Cervical Radiculopathy

- de Quervain tendinopathy

- EBM: Massage Therapy edit

- Endurance Athletes Common Conditions

- Endurance Athletes Overuse Injuries

- Finger injuries

- Foot Fractures

- Fractures: Foot

- Fractures in children

- Heel Pain

- Hip Pain in Adults

- Joint Injections

- Knee Pain

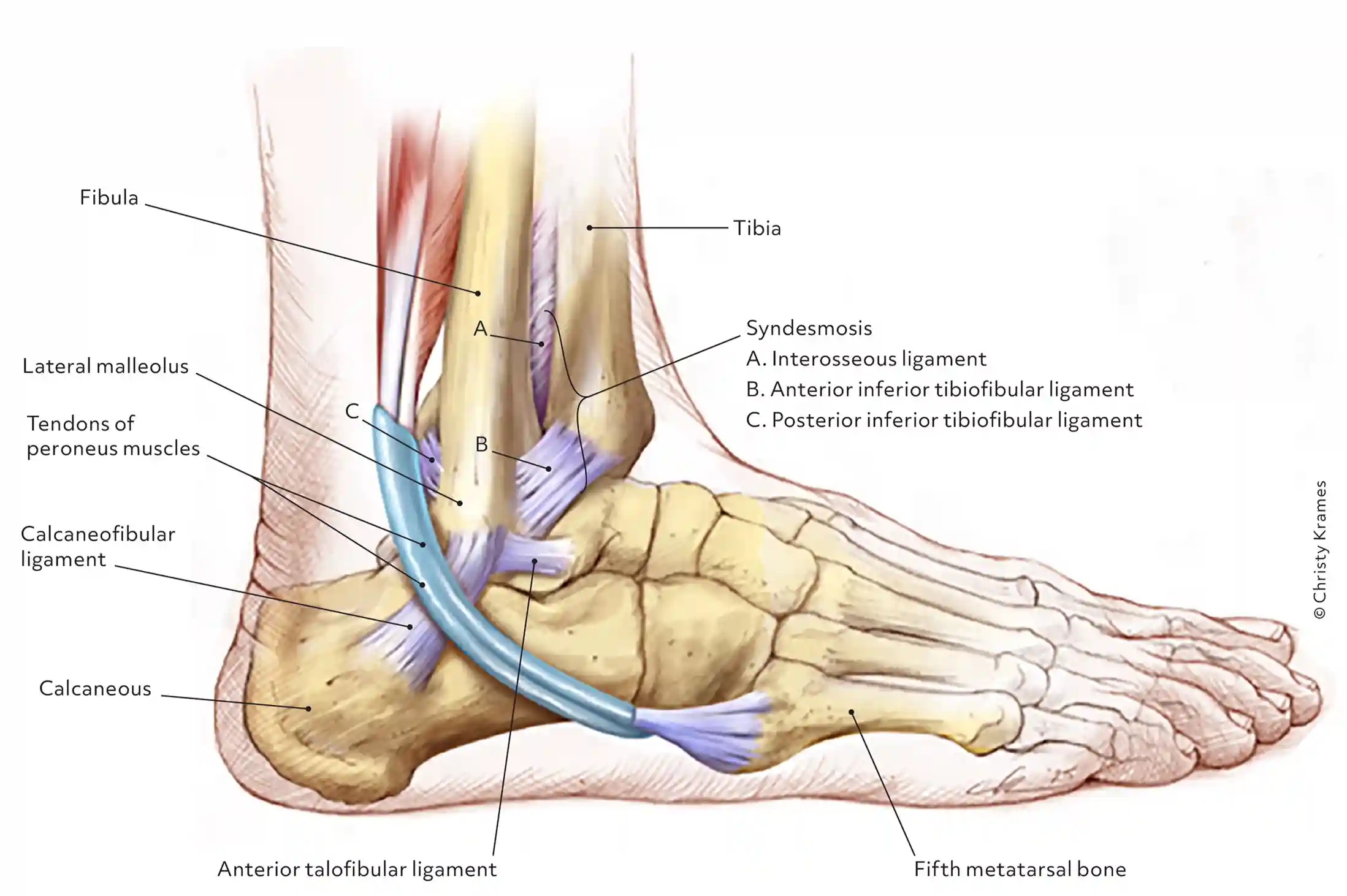

- Lateral ankle sprain

- Lateral/medial epicondyle pain

- Low back pain

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

- Medial Collateral Ligament injury (MCL)

- Morton's Neuroma

- MSK Exams

- MSK Tests

- Nocturnal Leg Cramps

- Osteoarthritis

- Overtraining Syndrome

- Overtraining Syndrome (Review for accuracy) edit

- Peripheral nerve entrapment (Upper Extremity)

- Physical activity

- Plantar fasciitis

- Platelet-rich Plasma (PRP)

- Prolotherapy

- Rehab

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (red-s) (Formerly Female Triad)

- Restless Leg Syndrome

- Running injuries

- Sacroiliac (SI) Joint Pain

- Shoulder

- Shoulder Impingement PT edit

- Sports Physicals

- Study: Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: Update Of An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline

- Study: Exercise Is the Only Intervention to Provide Long-Term Improvement in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain

- Tendinopathy

- Trigger Finger

- VO2 Max

- Walking/Steps Evidence

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Altitude Sickness edit

- Bell's Palsy edit

- Bells Palsy

- BPPV

- Cerebral Vascular Accident

- Cervical Nerve Roots

- Concussions

- Assessment Tools

- Management

- Management - Post-Concussion Headache

- Return to Play (Student)

- School Accommodations (Student)

- Return to Play (Adult)

- Study: Is rest after concussion "the best medicine?": Recommendations for activity resumption following concussion in athletes, civilians, and military service members

- Concussion Advice

- Concussion Recognition Tool

- New Orleans criteria for CT after minor head injury

- Classification Of Sports/Risk Categories

- Military Primary Care Concussion Management

- Q-Collar

- Cranial Hemorrhages

- Degenerative cervical myelopathy edit

- Dementia

- Dizziness

- Headaches

- Neurological Physical Examination

- Neurologic Exam Components

- Parkinson and Mimics

- Peripheral Neuropathy

- Seizures

- Syncope

- Tension Headache edit

- Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Temporal Arteritis

- Tremor

- Nutrition

- Beans/Legumes edit

- Biochemical Nutritional Indications

- Calories in Drinks and Popular Beverages

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2015-2020)

- Dietary patterns and changes

- Eat Nuts!

- EBM Food Intake and Diet

- Fats and Lipids

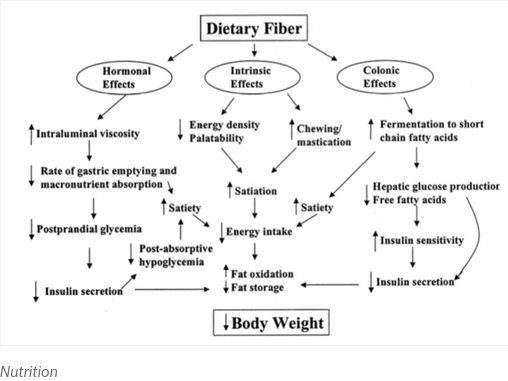

- Fiber

- FODMAP

- Food Intake Planning/Diets

- Guidance

- How Intermittent Fasting Affects Your Cells and Hormones

- Insulin and Weight

- Ketogenic Diet

- Low Glycemic Index

- Macronutrient Composition of Diet

- Macronutrient Ranges edit

- Mediterranean Diet edit

- Michi's Ladder of Healthy Food Choices edit

- Nutrition and Diet

- Optimizing foods for satiety edit

- Patient Messaging: General Nutrition Information

- Patient Messaging: Healthy food: 7 Affordable Ideas

- Patient Messaging: Intermittent Fasting (IF)

- Patient Messaging: Portion control

- Portions

- Recommended Daily Allowance for Macronutrients

- Recommended Nutrition For Muscle Injury

- Renal Diet/Lifestyle

- Study: Coffee and tea consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer: a pooled analysis of prospective studies from the Asia Cohort Consortium

- Study: Detox diets for toxin elimination and weight management: a critical review of the evidence

- Study: Dietary Sugar Intake and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies

- Study: Effect of Calorie Restriction on Mood, Quality of Life, Sleep, and Sexual Function in Healthy Nonobese Adults: The CALERIE 2 Randomized Clinical Trial

- Study: Optimal dietary patterns for healthy aging

- Study: Salad and satiety: energy density and portion size of a first-course salad affect energy intake at lunch

- Sugar

- Vegetarian Diets

- OB/GYN

- Advanced Lifesaving in Obstetrics (ALSO)

- Breast Cancer Risk Tool

- Breast Exam edit

- Breastfeeding

- Cervical Disease

- Chronic Pelvic Pain

- Colposcope Prediction: REID Index

- Contraindications to vaginal delivery

- Dysmenorrhea

- Dyspareunia

- EAB

- Abortion in Florida

- Study: Abortion, substance abuse and mental health in early adulthood: Thirteen-year longitudinal evidence from the United States

- Study: Emotions over five years after denial of abortion in the United States: Contextualizing the effects of abortion denial on women's health and lives

- Study: Global prevalence of post-abortion depression: systematic review and Meta-analysis

- Study: Perceived stress and emotional social support among women who are denied or receive abortions in the United States: a prospective cohort study edit

- Study: Socioeconomic Outcomes of Women Who Receive and Women Who Are Denied Wanted Abortions in the United States edit

- Study: Suicide risks associated with pregnancy outcomes: a national cross-sectional survey of American females 41-45 years of age

- Endometrial Biopsy

- Endometrial Thickness

- Fetal Monitoring

- GDM

- HCG Levels During Pregnancy

- Hormonal Contraceptives

- Hysterectomy Types

- Infertility

- IUD and Depression/Anxiety edit

- Study: Levonorgestrel intrauterine device and depression: A Swedish register-based cohort study

- Study: The potential association between psychiatric symptoms and the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs): A systematic review

- Study: Association Between Intrauterine System Hormone Dosage and Depression Risk

- Study: Cohort Study of Psychiatric Adverse Events Following Exposure to Levonorgestrel-Containing Intrauterine Devices in UK General Practice

- IUD Comparisons edit

- Kegel Instructions

- Limited OB Ultrasound (ALSO)

- Mammograms

- Menopause

- Menstrual Irregularities

- Natural Family Planning

- Nipple discharge

- Oral Contraception

- Pap Recommendations

- Pelvic Exams

- Pelvic Pain (Acute)

- Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

- Pregnancy status

- Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)

- Prenatal Care

- Progesterone Use edit

- Risk factors for post partum hemorrhage

- Sexual Dysfunction In Women

- Uterine Bleeding

- Vaginitis

- Weight gain in Pregnancy

- Ophthalmology

- Pain

- Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

- Facial pain

- Back pain

- Knee pain

- MSK Pain Guidelines edit

- Non-narcotic Medications

- Opioids

- Postherpetic neuralgia

- Resources

- Butrans (Buprenorphine Waiver Notification)

- CDC Opioids

- Controlled Meds edit

- Buprenorphone edit

- Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low‐back pain edit

- Understanding Buprenorphine for Use in Chronic Pain: Expert Opinion edit

- Urine Drug Testing edit

- Medication edit

- Monitoring Medication for Chronic Nonmalignant Pain edit

- Opioid Appropriate Documentation of Follow-up Visits edit

- CDC Opioid Recommendations edit

- Cannabis-Based Products for Chronic Pain edit

- Study: Physician Empathy and Chronic Pain Outcomes edit

- PDMP Overdose Risk Score edit

- Pediatrics

- 2023 Childhood Immunizations Edit

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children

- Acute Migraines in Children

- ADHD Pediatric Management

- Bruising/Non-accidental Trauma

- Child Development

- Children (<3 yo) with a Fever

- Constipation (Newborn)

- Constipation (Pediatric)

- Croup

- Dermatologic Concerns

- Documentation: Newborn Exam

- Febrile Seizures

- Feeding schedule

- Functional Abdominal Pain in Children

- Hypertension (Pediatric)

- Orlando Pediatric Resources

- Parenting

- Pediatric Depression edit

- Pediatric Dosing: acetaminophen

- Pediatric Dosing: cetirizine

- Pediatric Dosing: dextromethorphan

- Pediatric Dosing: diphenhydramine

- Pediatric Dosing: ibuprophen

- Pediatric Dosing: loratadine

- Sleep

- Transgender and Pediatrics

- Urinary Tract Infections in Children

- Vital Signs

- Down's Syndrome

- Study: Epinephrine metered-dose inhaler for pediatric croup

- Psychiatry

- Addiction and Dependence

- ADHD

- Anxiety

- Autism

- Bipolar Disorder

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- Dialectal Behavior Therapy

- Depression

- Drugs that can cause psychosis

- Eating Disorders

- Emotional Support Animals in Florida

- Generic ADHD Stimulants edit

- Illness Anxiety Disorder (Hypochondriasis)

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Personality Disorders

- Phobias

- Psychological Examination

- PTSD

- Sexual Dysfunction

- Somatic Symptom Disorder

- Study: Attending live sporting events predicts subjective wellbeing and reduces loneliness edit

- Study: Framing depression as a functional signal, not a disease: Rationale and initial randomized controlled trial

- Study: Ketamine versus ECT for Nonpsychotic Treatment-Resistant Major Depression

- Study: The brain structure, immunometabolic and genetic mechanisms underlying the association between lifestyle and depression edit

- Study: The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

- Study: Watching sport enhances well-being: evidence from a multi-method approach

- Study: Watching sports and depressive symptoms among older adults: a cross-sectional study from the JAGES 2019 survey

- Suicide

- Study: How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing

- Study: A dose response relationship between accelerometer assessed daily steps and depressive symptoms in older adults: a two-year cohort study

- Study: Daily Step Count and Depression in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Study: Efficacy and Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors, and Placebo for Common Psychiatric Disorders Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis edit

- Study: The efficacy of paroxetine and placebo in treating anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis of change on the Hamilton Rating Scales edit

- Study: Antidepressants versus placebo in major depression: an overview edit

- Study: Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care edit

- Study: Meta-analysis of the association between gratitude and loneliness edit

- Suicide Risk And Documentation

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Medications and Long-Term Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases

- Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

- Autism edit

- Study: Explaining the increase in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: the proportion attributable to changes in reporting practices

- Study: Trends in Autism Prevalence: Diagnostic Substitution Revisited

- Study: Gender Dysphoria Report edit

- Study: Mapping the genetic landscape across 14 psychiatric disorders

- Study: Exposing Worry’s Deceit: Percentage of Untrue Worries in Generalized Anxiety Disorder Treatment

- Pulmonary

- Asthma

- Chronic Cough

- COPD

- Dyspnea

- Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- Incidental Pulmonary Nodules detected on CT Images

- Lung Ca Screening

- Pneumonia

- Predicted Peak Expiratory Flow (L/min)

- Pulmonary Function Tests

- Pulmonary Nodules

- Sleep and Insomnia

- Developmental Sleep Recommendations

- Chronic Insomnia

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- Sleep Hygiene Rules for the treatment of insomnia

- Sleep Restriction Therapy:

- The Army Quick Sleep Technique

- 4-6-7 Breathing Technique Will Knock You Out in 10 Minutes Flat

- Ways to get more sleep

- Jet Lag edit

- Sleep Study Results Explanation

- Sleep Duration Recommendations

- Study: A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale

- Study: Sleep duration and mortality: a prospective study of 113 138 middle-aged and elderly Chinese men and women

- Sleep Cycles and Napping edit

- Study: Sleep loss and emotion: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 50 years of experimental research

- Patient Messaging: Avoiding Fatigue

- Spirometry

- Taking a nap (30/90 Rule)

- Tobacco (Smoking Cessation)

- Cytisine for Smoking Cessation, cheaper alternative to Chantix

- E-cigarette's users twice as likely to quit smoking

- Health Benefits After Quitting:

- Management

- Smoking and supplements

- Smoking USPSTF

- Tools, Apps, Resources

- Vaping and nicotine

- Smoking Cessation Messaging

- Smoking Cessation with patch edit

- Vocal Cord Dysfunction

- Radiology

- Rheumatology

- Studies: Activity and Exercise

- Evidence on Running

- Evidence regarding the Q collar

- Exercise As Medicine

- Patient Messaging: Exercise and Strength Building

- Stair Climbing

- Energy cost of walking and running at extreme uphill and downhill slopes

- Study: Brief Intense Stair Climbing Improves Cardiorespiratory Fitness

- Study: Energy cost of stair climbing and descending on the college alumnus questionnaire

- Study: The Energy Expenditure of Stair Climbing One Step and Two Steps at a Time: Estimations from Measures of Heart Rate

- Steps Daily edit 2025

- Study: Antidepressants or running therapy: Comparing effects on mental and physical health in patients with depression and anxiety disorders

- Study: Association of Daily Step Count and Intensity With Incident Dementia in 78,430 Adults Living in the UK

- Study: Association of Daily Step Patterns With Mortality in US Adults

- Study: Association of Timing of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity With Changes in Glycemic Control Over 4 Years in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes From the Look AHEAD Trial

- Study: Association of wearable device-measured vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity with mortality

- Study: Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness in youth and the incidence of site-specific cancer in men: a cohort study with register linkage

- Study: Cardiorespiratory fitness is a strong and consistent predictor of morbidity and mortality among adults: an overview of meta-analyses representing over 20.9 million observations from 199 unique cohort studies

- Study: Clinic and Park Partnerships for childhood resilience: A prospective study of park prescriptions

- Study: Daily Step Count and Depression in Adults - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Study: Daily Steps And Health Outcomes In Adults: A Systematic Review And Dose-Response Meta-Analysis

- Study: Do the associations of daily steps with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease differ by sedentary time levels? A device-based cohort study

- Study: Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an individualised, progressive walking and education intervention for the prevention of low back pain recurrence in Australia (WalkBack): a randomised controlled trial

- Study: Effect of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity on All-Cause Mortality in Middle-aged and Older Australians

- Study: Effects of various exercise interventions in insomnia patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

- Study: Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men

- Study: Exercise training enhances muscle mitochondrial metabolism in diet-resistant obesity

- Study: Exploring the Relationship between Walking and Emotional Health in China

- Study: Higher resistance training volume offsets muscle hypertrophy nonresponsiveness in older individuals

- Study: Long-term time-course of strength adaptation to minimal dose resistance training: Retrospective longitudinal growth modelling of a large cohort through training records

- Study: Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods

- Study: Move less, spend more: the metabolic demands of short walking bouts

- Study: Movement Is Medicine: Structured Exercise Program May Lower Risk of Cancer Recurrence and Death for Some Colon Cancer Survivors

- Study: Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes:s a dose–response meta-analysis of large prospective studies

- Study: Oral Salt Supplementation During Ultradistance Exercise

- Study: Progression Models in Resistance Training for Healthy Adults

- Study: Relationship of Daily Step Counts to All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events

- Study: Resistance Exercise Training in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease: 2023 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association edit

- Marathon/Ultramarathon Endurance Related

- Study: Effect of Sodium Supplements and Climate on Dysnatremia During Ultramarathon Running

- Study: Different Predictor Variables for Women and Men in Ultra-Marathon Running—The Wellington Urban Ultramarathon 2018

- Study: Changes in Pain and Nutritional Intake Modulate Ultra-Running Performance: A Case Report edit

- Study: Effects of 120 g/h of Carbohydrates Intake during a Mountain Marathon on Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage in Elite Runners

- Study: Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia, Hypernatremia, and Hydration Status in Multistage Ultramarathons

- Study: Fluid Replacement during Marathon Running

- Study: Limits of Ultra: Towards an Interdisciplinary Understanding of Ultra-Endurance Running Performance edit

- Study: Predictor Variables for A 100-km Race Time in Male Ultra-Marathoners edit

- Study: Sleep and Subjective Recovery in Amateur Trail Runners After the Ultra-Trail du Mont Blanc® (UTMB®)

- Study: The Training Intensity Distribution of Marathon Runners Across Performance Levels

- Study: Ultra-Marathon Nutrition

- Study: Widespread drastic reduction of brain myelin content upon prolonged endurance exercise edit

- Study: Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men

- Study: Screen-based entertainment time, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular events: population-based study with ongoing mortality and hospital events follow-up

- Study: Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Study: Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing

- Study: Stair walking is more energizing than low dose caffeine in sleep deprived young women

- Study: Structured Exercise after Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer

- Study: The Acute Effects of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting Time in Adults with Standing and Light-Intensity Walking on Biomarkers of Cardiometabolic Health in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Study: The associations of "weekend warrior" and regularly active physical activity with abdominal and general adiposity in US adults

- Study: The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

- Study: Timing of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity, Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Microvascular Disease in Adults With Obesity

- Study: Vigorous Intermittent Lifestyle Physical Activity and Cancer Incidence Among Nonexercising Adults

- Study: Walking as an intervention to reduce blood pressure in adults with hypertension: recommendations and implications for clinical practise

- Study: Walk to a Better Night of Sleep: Testing the Relationship Between Physical Activity and Sleep

- Walking and energy use edit

- Walking increases life expectancy by 3.4-4.5 years - Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis

- Water/Electrolyte Balance Table

- Study: Are There Deleterious Cardiac Effects of Acute and Chronic Endurance Exercise?

- Study: Association between physical activity and risk of incident arrhythmias in 402,406 individuals: Evidence from the UK Biobank cohort

- Studies: COVID-19 Related

- Infection and Fatality Rates

- Study: The infection fatality rate of COVID-19 inferred from seroprevalence data (For those <70 yo ->0.00-0.57%)

- Study: Age-stratified infection fatality rate of COVID-19 in the non-elderly informed from pre-vaccination national seroprevalence studies

- Study: Community transmission (Vaccinated vs Unvaccinated)

- Study: Ct values and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces

- Lockdowns

- Natural Immunity

- Study: Natural Immunity is better than Vacinated Immunity against Delta Variant

- Study: Past SARS-CoV-2 infection protection against re-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Study: Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: a systematic review and meta-regression

- Origin

- Prevention

- Study: Possible toxicity of chronic carbon dioxide exposure associated with face mask use, particularly in pregnant women, children and adolescents – A scoping review

- Study: Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses (Chochrane review of masks)

- Study: FXR inhibition may protect from SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing ACE2 (urodiol/actigall)

- Study: Japan supercomputer shows doubling masks offers little help preventing viral spread

- Study: Wastewater-based monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 at UK airports and its potential role in international public health surveillance (COVID travel restrictions on flying were a total failure)

- Study: N95 Respirators vs Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel (RCT)

- Study: Effectiveness of Adding a Mask Recommendation to Other Public Health Measures to Prevent SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Danish Mask Wearers (RCT)

- Study: Correlation Between Mask Compliance and COVID-19 Outcomes in Europe

- Study: Modeling the filtration efficiency of a woven fabric: The role of multiple lengthscales

- Study: Revisiting Pediatric COVID-19 Cases in Counties With and Without School Mask Requirements—United States, July 1—October 20 2021

- Study: Mask mandate and use efficacy in state-level COVID-19 containment

- Study: Associations of Physical Inactivity and COVID-19 Outcomes Among Subgroups (Physically active = less COVID symptoms)

- Study: Medical Masks Versus N95 Respirators for Preventing COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers (No difference)

- Study: Child mask mandates for COVID-19: a systematic review

- Study: Coffee as a dietary strategy to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection edit

- Risk Factors

- Sequelae

- Study: Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 associates with physical inactivity in a cohort of COVID-19 survivors

- Study: Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

- Study: COVID-Specific Long-term Sequelae in Comparison to Common Viral Respiratory Infections: An Analysis of 17 487 Infected Adult Patients (The 7 Long Covid Symptoms)

- Study: Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations

- Study: Machine learning links unresolving secondary pneumonia to mortality in patients with severe pneumonia, including COVID-19

- Study: Orthostatic tachycardia after covid-19

- Study: COVID does not increase incidence of neither pericarditis nor myocarditis

- Study: SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers pro-atherogenic inflammatory responses in human coronary vessels edit

- Testing

- Treatment

- Study: Antidepressant drug prescription and incidence of COVID-19 in mental health outpatients: a retrospective cohort study

- Study: Discriminatory Attitudes Against the Unvaccinated During a Global Pandemic

- Study: Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants

- Study: Effectiveness of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Bivalent Vaccine

- Study: Evaluation of Waning of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine–Induced Immunity

- Study: Vaccines and Serious Adverse Effects Rate

- Study: Sex-specific differences in myocardial injury incidence after COVID-19 mRNA-1273 Booster Vaccination

- Study: Aerobic exercises recommendations and specifications for patients with COVID-19: a systematic review

- Study: Association between vitamin D supplementation and COVID-19 infection and mortality edit

- Study: IgG4 Antibodies Induced by Repeated Vaccination May Generate Immune Tolerance to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein

- Study: Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting

- Study: Exercise May Improve Fatigue Associated With Long COVID in Active Young Adults

- Study: Surveillance of COVID-19 vaccine safety among elderly persons aged 65 years and older (Temporal association with PE, AMI, DIC, and ITP)

- Study: Fenofibrate

- Study: Outcomes after early treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: An analysis of a database of 30,423 COVID-19 patients

- Study: The role of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing post-COVID-19 thromboembolic and cardiovascular complications edit

- Study: Analysis of the Association Between BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination and Deaths Within 10 Days After Vaccination Using the Sex Ratio in Japan edit

- Study: OpenSAFELY: Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in children and adolescents

- Study: An analysis of studies pertaining to masks in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Characteristics and quality of all studies from 1978 to 2023 edit

- Study: A Critical Analysis of All-Cause Deaths during COVID-19 Vaccination in an Italian Province

- Study: Post Conditional Approval Active Surveillance Study Among Individuals in Europe Receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine

- Study: Postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in the population: Risk factors and vaccines

- Study: Rates of successful conceptions according to COVID-19 vaccination status: Data from the Czech Republic

- Study: The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on vaccinated versus unvaccinated pregnant women: a retrospective cohort study

- Study: Impact of mRNA and Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccines on Ovarian Reserve

- Infection and Fatality Rates

- Studies: Marijuana

- Study: Association of Cannabis Use With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among US Adults

- Study: Brain Function Outcomes of Recent and Lifetime Cannabis Use

- Study: Cannabinoids, cannabis, and cannabis-based medicine for pain management: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials

- Study: Cannabis Use Disorder and Subsequent Risk of Psychotic and Nonpsychotic Unipolar Depression and Bipolar Disorder

- Study: Daily Marijuana Use is Associated With Incident Heart Failure: "All of Us" Research Program edit

- Study: Evaluating the impact of cannabinoids on sleep health and pain in patients with chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Study: Frequent marijuana use linked to heart disease

- Study: Incident testicular cancer in relation to using marijuana and smoking tobacco: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies

- Study: Increased Risk of Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Events in Elderly Non-Smokers With Cannabis Use Disorder: A Population-Based Analysis edit

- Study: Marijuana linked to higher PAD risk

- Study: Myocardial Infarction and Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Cannabis Use: A Multicenter Retrospective Study

- Study: Nondisordered Cannabis Use Among US Adolescents

- Study: The placebo response in cannabinoid trials for clinical pain

- Studies: Weight Management

- Patient Messaging: Bariatric Surgery

- Reference: Weight Watcher's to Calorie Conversion edit

- Study: Alternate Day Fasting Combined With Endurance Exercise for the Treatment of Fatty Liver Disease

- Study: A population-based study of appetite-suppressant drugs and the risk of cardiac-valve regurgitation

- Study: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of the long-term efficacy and safety of diethylpropion in the treatment of obese subjects

- Study: Association between insulin sensitivity and lean mass loss during weight loss

- Study: Brain responses to nutrients are severely impaired and not reversed by weight loss in humans with obesity: a randomized crossover study

- Study: Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss

- Study: Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men

- Study: Consumption of Soft Drinks and Overweight and Obesity Among Adolescents in 107 Countries and Regions

- Study: Continued Treatment With Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults With Obesity

- Study: Dietary Macronutrient Composition and Protein Concentration for Weight Loss Maintenance

- Study: Diets for weight management in adults with type 2 diabetes: an umbrella review of published meta-analyses and systematic review of trials of diets for diabetes remission

- Study: Does time-restricted eating add benefits to calorie restriction? A systematic review edit

- Study: Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss

- Study: Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and other weight loss drugs in overweight and obesity: a network meta-analysis

- Study: Energy expenditure and obesity across the economic spectrum

- Study: Healthy weight loss maintenance with exercise, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or both combined followed by one year without treatment: a post-treatment analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial edit

- Study: Host-diet-gut microbiome interactions influence human energy balance: a randomized clinical trial

- Study: Impact of weight loss achieved through a multidisciplinary intervention on appetite in patients with severe obesity edit

- Study: Incident type 2 diabetes attributable to suboptimal diet in 184 countries

- Study: Increased Physical Activity Associated with Less Weight Regain Six Years After "The Biggest Loser" Competition

- Study: Less frequent dosing of GLP-1 receptor agonists as a viable weight maintenance strategy

- Study: Lifestyle Strategies after Intentional Weight Loss: Results from the MAINTAIN-pc Randomized Trial

- Study: Liraglutide versus semaglutide for weight reduction—A cost needed to treat analysis

- Study: Low-calorie diet-induced weight loss is associated with altered brain connectivity and food desire in obesity

- Study: Modeling potential cost-effectiveness of tirzepatide versus lifestyle modification for patients with overweight and obesity

- Study: Nut consumption, gut microbiota, and body fat distribution: results of a large, community-based population study

- Study: Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition

- Study: Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- Study: Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with weight-loss attempts and perception of overweight independent of BMI: a population-based cohort study

- Study: Reducing Social Media Use Improves Appearance and Weight Esteem in Youth With Emotional Distress

- Study: RE: Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Use of Phentermine?

- Study: Semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk for weight loss in patients with severe obesity and with or without a history of bariatric surgery

- Study: Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials

- Study: The association between weight loss medications and cardiovascular complications

- Study: The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years

- Study: Three- and six-month efficacy and safety of phentermine in a Mexican obese population

- Study: Time-Restricted Eating Without Calorie Counting for Weight Loss in a Racially Diverse Population

- Study: Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity

- Study: Triple–Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity — A Phase 2 Trial

- Study: Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension edit

- Weight and Psychiatric Medications edit

- Study: People With Lowest Physical Functioning Scores Showed Greatest Improvement After Tirzepatide Treatment

- Study: Obesity as a Risk Factor for Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Wegovy Studies

- Study: Addition of Phentermine-Topiramate to a Digitally Enhanced Lifestyle Intervention: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial

- Study: Weight regain after cessation of medication for weight management: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Study: Energy expenditure and obesity across the economic spectrum

- Trauma/Emergency

- Urology

- Acute simple cystitis in women (Simple UTI)

- Bladder Cancer

- BPH

- Common Causes of Abnormal Urine Coloration

- Erectile Dysfunction

- Hematuria

- Incontinence edit

- Infertility (Male)

- Interstitial Cystitis and Bladder Pain Syndrome

- Male Hormones 2025

- Men's Health

- Nephrolithiasis

- Nocturia

- Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA)

- Semen

- Study: Efficacy of Clomiphene Citrate Versus Enclomiphene Citrate for Male Infertility Treatment: A Retrospective Study

- Uncomplicated cystitis

- Urinary Tract Infections

- Weight Management/ABCD

- 5 A's of discussing Obesity/ABCD

- Weight Loss Success Strategies

- - (1) - Identify appropriate patients who need to lose weight

- - (2) - Physical Assessment

- - (3) - Screening

- - (4) - Treat Comorbidities

- Medical and psychosocial consequences of obesity

- Obesity and Atrial Fibrilation

- Obesity and Cancer

- Obesity and Gall bladder disease

- Obesity and Heart Disease

- Obesity and Hypertension

- Obesity and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

- Obesity and Psychosocial impact

- Obesity and Sleep

- Obesity and Sleep Apnea

- Obesity and Stroke

- Obesity Paradox - Things made worse with weight loss

- - (5) - Lifestyle modification

- - (6a) - Pharmacotherapy

- - (6b) - Bariatric surgery

- - (7) - Maintenance of Weight Loss and Prevention of Weight Regain

- Basics of all practice guidelines:

- Coding for Weight Loss

- Epidemiology and physiology

- Medicine Quotes

- Pediatric Obesity

- Pregnancy and Weight

- Resources

- Patient Messaging

- Org

- CBD Autism

- Anxiety Stuff and Messaging edit

- Anxiety Messaging

- General Anxiety Strategies:

- CBT edit

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Face your fears (Graded Exposure)

- Challenge your thoughts

- Calming imagery

- Time Management Strategies

- Do Stretches

- Mindful Breathing

- Name that emotion

- Relaxation Strategies

- Challenge your Negative Thoughts edit

- Decatastrophizing edit

- Cognitive Distortions

- 9 Essential CBT Techniques and Tools

- Diabetes Care Standards (2024) edit

- ADHD Stuff to Edit

- Core CBT Techniques

- DM with Hemoglobinopathies

- Male Infertility

- AF

- Asymptomatic Hypertension

- Chronic Urticaria

- Osteoporosis

- Minimal Exercise Necessary edit

- Overcome Social Anxiety edit

- Study: Objective assessment of health or pre-chronic disease state based on a health test index derived from routinely measured clinical laboratory parameters

- To Capture edit 2025

- Study: Role of Inactivity in Chronic Diseases: Evolutionary Insight and Pathophysiological Mechanisms

- Study: Optimism is associated with exceptional longevity in 2 epidemiologic cohorts of men and women

- homocysteine

- Follow up: HRT testosterone edit 2025

- Helping healthy people? edit 2025

- Study: Why more social interactions lead to more polarization in societies

- Counselors edit 2025

- Pompe Disease edit

- Study: Open-label placebos—a systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies with non-clinical samples edit

- Study: Listening to Prozac but hearing placebo: A meta-analysis of antidepressant medication edit

- Study: Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data edit

- Study: The effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials edit

- Study: Risk of suicide, suicide attempt, and suicidal ideation among people with vitamin D deficiency: a systematic review and metaanalysis edit

- Effect sizes on Depression edit

- Study: Cholesterol-lowering effects of oats induced by microbially produced phenolic metabolites in metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial edit

- Study: Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Use in Elderly People With Obesity—A Meta-Analysis

Aesthetics

Botox/Xeomin Injections (botulinum toxin type A)

Good article: Botulinum toxin in facial plastic surgery

General Techniques:

- Inject while retracting

- Patient in a 60 degree recline

- Touch up 2 weeks later if needed

- Use white eyeliner to mark safety zones

- Compress injection sites firmly away into safety zone

- Wipe area with EtOH swab

- Inject with muscles contracted (Frown and Forehead)

| Botox | Xeomin | Disport | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equiv Units | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Diffusion Rate | + | ++ | |

| Results show | 4-5 | 3-5 | 2-3 |

| Price/unit | $$ | $$ | $ |

| Price Overall | $$ | $$ | $$ |

| Allergens to avoid | egg/latex |

Reconstitution

| 50 unit vial | 100 unit vial | 200 unit vial | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9% NaCl* | 2.5 mL | 5 mL | 10 mL |

*Preservative Free

Reconstitution and Dilution - Flip It. Don't Shake It.

- Prior to injection, reconstitute each vial of XEOMIN with sterile, preservative-free 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection

- A 20 to 27-gauge short-bevel needle is recommended for reconstitution

- Draw up an appropriate amount of preservative-free 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP into a syringe

Steps:

- Step 1: Vial preparation

- Clean the exposed portion of the rubber stopper of the vial with alcohol (70%) prior to insertion of the needle.1

- Step 2: Saline injection

- After vertical insertion of the needle through the rubber stopper, the vacuum will draw the saline into the vial. Gently inject any remaining saline into the vial to avoid foam formation. If the vacuum does not pull the saline into the vial, then XEOMIN must be discarded.1

- Step 3: Mixing

- Remove the syringe from the vial and mix XEOMIN with the saline by carefully swirling and inverting/flipping the vial—do not shake vigorously.1

Frown Lines

Injection sites:

- 1 cm above eyebrow (orbital rim) at the medial edge of eye line (medial Canthus) (Corrugator muscle)

- 2 - 4 u each side

- 1 cm above eyebrow (orbital rim) on the medial edge of the iris line (Limbus) (Corrugator muscle)

- 2 u each side

- Standing in front of patient, inject into Procerus muscle

- Imagine an X from medial canthus to Corrugator injection (#1)

- 4 u (2.5 - 5 u)

Total dose:

- Women: 20 units

- Men: 25 units

Reference:

Forehead Lines

General Injection Strategy:

- Superior half to third of forehead inject 2 units symmetrically in ridges (not valleys) (Frontalis muscle)

- Consider 4 sites in horizontal line

- 2 units each (8 total)

- If needed add another line in a ridge consisting of 2- 3 sites in spaces between previous injections

- Might look best if in a V shape

- 2 units each (4 to 6 units)

- Approach with 30 degree angle

Total dose:

- Women: 15 - 20 units

- Men: 20 - 25 units

Botox Aftercare Instructions

Aftercare instructions:

- No physical exercise (24 hours)

- Avoid heat exposure (24 hours)

- Avoid alcohol and painkillers

- Don't wear anything on the treatment area

- No laying down after your Botox treatment (4 hours); Also, avoid sleeping on your face for at least 1 night

- No touching your face or massaging the treatment area

Injection Plan:

- Use 8 units Glabellar

- 4 u Precerus

- 2 u Bilat Corrugator

- Use 12 units Forehead

- 1 line of 4 sites

- 1 line of 2 sites (if needed) . . . . . .

Botox FAQ

How long is BOTOX good for after reconstitution?

Ideally you will want to use the reconstituted vial of botulinum toxin within 3 weeks, however it can last up to eight weeks when stored properly in the fridge (Hexcel et al 2003). What is the standard dilution for BOTOX?

The recommended dose is 100 Units of BOTOX, and is the maximum recommended dose. The recommended dilution is 100 Units/10 mL with preservative-free 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, USP (see Table 1).

Does BOTOX require reconstitution?

BOTOX® Cosmetic dilution and reconstitution processes are the same for moderate to severe forehead lines, lateral canthal lines, and glabellar lines. Note: once open and reconstituted, use within 24 hours, because product and diluent do not contain a preservative. How do you store BOTOX after reconstitution?

BOTOX should be administered within 24 hours after reconstitution. During this time period, reconstituted BOTOX should be stored in a refrigerator (2° to 8°C).

What is Botox reconstitution?

Allergan advocates 100 U of BOTOX® diluted in 2 cc of preservative-free normal saline, which results in a concentration of 5 U/per 0.1 mL. Reconstitution is performed using a vial of BOTOX®, which must remain upright. A 21-gauge, 2-inch needle is attached to a 5 mm syringe.

Reference:

Allergy/Immunology

Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis

- An immunoglobulin E–mediated process

Preventions that don't work

- High-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters are not effective at decreasing allergy symptoms.

- Dust mite–proof mattress covers do not prevent allergic rhinitis in children two years and younger.

History

- Whether the symptoms are seasonal or perennial

- Symptom triggers

- Severity

Common examination findings

- Clear rhinorrhea

- Pale nasal mucosa

- Swollen nasal turbinates

- Watery eye discharge

- Conjunctival swelling

- Allergic shiners

Testing:

- Serum or skin testing for specific allergens should be performed when there is inadequate response to empiric treatment, if diagnosis is uncertain, or to guide initiation or titration of therapy.

- If allergy testing is performed, trigger-directed immunotherapy can be effectively delivered subcutaneously or sublingually

Treatment

- Intranasal corticosteroids are first-line treatment for allergic rhinitis.

- Second-line therapies include antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists and neither shows superiority.

Approximately 1 in 10 patients with allergic rhinitis will develop asthma.

Reference:

- Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(5):466-473

Anaphylaxis

USE epinephrine!

- Corticosteroids and diphenhydramine help stave off rebound anaphylaxis

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- Empiric 6 food elimination diet (SFED) resolves inflammation in 66% of patients

- Milk, Wheat, Soy, Eggs, Treenuts/peanuts, and fish/shellfish

- Food elimination based on allergy testing resolves esophageal inflammatiton in 50% of patients

- Often (69%), patients are able to identify a single food trigger

- Medication options for eosinophilic esophagitis include

- Topical steroids delivered via an asthma inhaler and then swallowed

- PPI

- Dysphagia with eosinophilic esophagitis is often secondary to esophageal strictures, which can be treated with endoscopic dilation

Causes:

- Dairy: 50%

- Wheat: 31%

- Soy

- Egg: 36%

- Nuts

- Fish/Shellfish

References:

- AFP Vol 103 No 9 May 2021

- Zalewski A, Doerfler B, Krause A, Hirano I, Gonsalves N. Long Term Outcomes of the Six Food Elimination Diet and Food Reintroduction in a Large Cohort of Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Aug 12. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001949. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35971213.

There are quite a few studies on a 4-6 food elimination diet to help with food allergies and sensitivities.

This is the process:

- Take the top 6 most common food allergens out of your diet for 6 weeks (milk products, eggs, wheat, soy, peanut/tree nuts, and fish/shellfish).

- At 6 weeks into the diet, review your symptoms.

- Bring the foods back into your diet, one at a time, for a 2 week trial each. See if you have any symptoms from them - if so, avoid their use.

Food Allergies

9 foods are responsible for the majority (90%) of allergic reactions:

- Cow's milk: cheese, yogurt, baked goods

- Eggs: mayonnaise, pasta, baked goods

- Fish: salmon, tuna, sauces

- Peanuts: peanut butter, sauces, candies

- Sesame: Seeds, tahini, bread

- Shellfish: shrimp, crab, lobster

- Soy: tofu, soy milk, soy sauce

- Tree nuts: almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, pistachios

- Wheat: Bread, pasta, processed foods

Risk factors (OR):

- Latex allergy (7.9)

- Asthma (3.2)

- Urticaria (2.9)

- Insect venom allergy (2.50

- Allergic rhinitis (2.3)

- Atopic dermatitis (1.9)

- Medication allergy (1.9)

Reduce risk:

- Early introduction of peanuts, cow's milk, wheat, and cooked eggs between 4-6 mo decreases risk of developing food allergies

- Early introduction of peanuts and cooked eggs at 4-6 mo is safe and effective for reducing risk of food allergy

| Airborne allergen | Food |

|---|---|

| Birch pollen | carrots, celery, fresh fruit, hazelnuts, parsnips, potatoes |

| Grass pollen | kiwi, tomatoes |

| Ragweed pollen | bananas, melons |

Reference:

- AFP Vol 108 No 2 Aug 2023

- https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-treatments/allergies/food-allergy

Seasonal Allergies

Allergy Medications

- Antihistamines: These medications are commonly used to treat allergies such as allergic rhinitis or sometimes urticaria (hives).

- Immunomodulator Medications: These medications act by directly changing the behavior of the immune system. These are also known as biological medications.

- Leukotriene Modifiers: These medications are used for relief of allergic rhinitis symptoms.

- Nasal Sprays and Sinus Medications: This table includes the various nasal sprays approved to treat allergic rhinitis and/or non-allergic rhinitis.

- Devices: This includes information on devices that have been approved for use to treat or manage allergic rhinitis.

- Eye Drops: This table lists the medications available to treat allergic conjunctivitis (allergic eye).

- Allergic Emergency Medications: These are the medications used to treat anaphylaxis.

- Topical Ointments & Creams: Here are the topical medications used to treat conditions such as atopic dermatitis and eczema.

- Treatment of Hereditary Angioedema: Replacement therapy or immune modulating medicines pertaining to hereditary angioedema.

- Oral Corticosteroids: These medications are sometimes used to treat severe allergies and can also be used as a rescue medication for asthma.

- Sublingual Immunotherapy (SLIT) Allergy Tablets: Allergy tablets are another form of allergy immunotherapy therapy and involves administering the allergens under the tongue generally on a daily basis.

To manage allergy symptoms, these are the medications with the strongest evidence:

- Flonase (fluticasone) spray (or similar like Nasocort) 2 sprays in each nostril daily. This takes at least a week of use before you will notice it working. To use, look down touching chin to chest, Spray into nose use other side arm (for example: left arm on right side)

- There is one antihistamine nasal spray which will help symptoms very quickly: Astepro allergy (azelastine)

- Also helpful are medications like: Allegra, Claritin, or Zyrtec. I find Allegra to be stronger than Claritin and Zyrtec. Use this every day when allergies are worse.

- To manage excessive congestion, you can use Sudafed 30-60 mg every 4 hours as needed. This medication might keep you awake, so be cautious with use at night.

My recommended maximal allergy management would be:

- Flonase daily

- Allegra-D (generic is fine)

- Astepro allergy (OTC antihistamine nasal spray)

IgG vs IgM

IgM

- IgM antibodies are produced by the body immediately after the exposure to a specific antigen

- Mainly found in blood and lymph fluid

- Quantity produced upon exposure to the antigen is nearly 6 times as much of IgG

- IgM antibodies usually also have 10 binding sites (compared to only 2 in IgG)

- Only about half of the binding sites can actually be used to bind IgM to an antigen

- IgM is multivalent: Multiple monomers are bonded together

- Temporary - disappear within 2 to 3 weeks following infection

IgG

- IgG refers to an immunity for a particular disease

- A late stage response as compared to IgM

- Abundant in the body

- Protects against various disease causing foreign agents

- IgM antibodies are replaced by IgG antibodies that last for life time

Systemic reaction to insect sting

- Evaluate patients with skin testing

- If positive: treat with venom immunotherapy

Reference:

- AFP Vol 106 No 6 Dec 2022

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS)

Symptoms - The symptoms most consistent with anaphylaxis are:

- Heart related symptoms: rapid pulse (tachycardia), low blood pressure (hypotension) and passing out (syncope).

- Skin related symptoms: itching (pruritus), hives (urticaria), swelling (angioedema) and skin turning red (flushing).

- Lung related symptoms: wheezing, shortness of breath and harsh noise when breathing (stridor) that occurs with throat swelling.

- Gastrointestinal tract symptoms: diarrhea, nausea with vomiting and crampy abdominal pain.

Reference:

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria for mast cell activation syndrome

According to the algorithm proposed by Valent et al, MCAS should be considered when the following 3 criteria are met:

- Presence of typical and recurrent severe symptoms of excess MC activation (often diagnosed as anaphylaxis affecting at least 2 organs).

- The typical symptoms include

- Urticaria

- Flushing

- Pruritus

- Wheezing

- Angioedema

- Nasal congestion

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Diarrhea

- Headaches, memory loss, and impaired concentration may also be observed, although these symptoms are less specific.

- The typical symptoms include

- Confirmed excess of MC activation in biochemical tests. The preferred marker is tryptase (elevated serum levels by 20% above the upper limit of the normal range or by at least 20% above baseline plus 2 ng/ml within 4 hours after a symptomatic period). Other metabolites include serum and urinary histamine and urine prostaglandin D2, leukotrienes C4 and E4, and 11β-prostaglandin F2α. Prostaglandin D2 in 24-hour urine collection is considered the most specific marker of excess MC activation, but its availability is highly limited.

- Positive response to symptom treatment as in mastocytosis. By consensus, this criterion should be fulfilled by antihistamine agents; however, response to other drugs, such as leukotriene receptor blockers, systemic glucocorticoids, and sodium cromoglycate, may also be useful, although they are considered less specific and thus more efficient in other diseases than MCAS. The withdrawal of symptoms should be complete or at least major, as self-reported by patients.

In the case of nonsevere, transient symptoms (criterion 1 not fulfilled) and positive criteria 2 and 3, systemic or local (if the range of skin symptoms is limited) mast cell activation (MCA) is diagnosed with a similar clinical approach to that in MCAS. In other cases, if the patient does not respond to standard MCAS treatment and requires repeated epinephrine administration, MCA might be diagnosed provided that typical symptoms (criterion 1) and elevated levels of MC-derived mediator (criterion 2) are present and the criteria for primary MCAS are met (see below).

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, MCAS is classified according to an underlying cause. Primary MCAS involves monoclonal MC proliferation, similar to SM but not fulfilling its criteria. In this type of MCAS, CD25+ mastocytes, the KIT D816V mutation, or both are observed in bone marrow biopsy. The diagnosis of mastocytosis is superior to that of MCAS, which means that if at any point the criteria for mastocytosis are fulfilled, MCAS is no longer considered. Secondary MCAS is defined as MC activation due to comorbidities.8 The most typical cause is type 1 hypersensitivity according to the Gell and Coombs classification, which leads to persistent MC activation through allergen-specific IgE.9 Hymenoptera venom, food, and drug intolerance or allergies are currently discussed as the most important causes of secondary MCAS. Although receptors for IgE (FcεRI) are considered the strongest MC activator, many different receptors are present on cell surface.10 Bacterial components might activate MC directly with toll-like receptors 2, 3, 4, and 6 as well as fMLP receptor or through complement activation.11 Excess of hormones may also induce secondary MCAS through estrogen, progesterone, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone receptors. The chronic use of certain drugs such as opioids, muscle relaxants, intravenous contrast media, or adenosine may also activate MCs. If the primary and secondary causes are excluded, idiopathic MCAS may be diagnosed.

Importantly, some patients may be diagnosed with primary and secondary MCAS, as is the case in patients with mastocytosis and insect venom allergy (IVA) who require specific lifelong immunotherapy.12,13 It is recommended that these patients are provided with lifelong immunotherapy, in addition to antimediator treatment and an emergency kit including at least 2 epinephrine autoinjectors.

Labs

The most important first-line examination in patients with suspected mastocytosis or primary MCAS is the measurement of tryptase levels in peripheral blood.19 In the absence of urticaria pigmentosa, the patient with the tryptase level below 15 ng/ml and no increase during the suspected reaction should be followed. The tryptase level above 25 ng/ml is an indication for bone marrow studies including histopathology, cytology, flow cytometry, and detection of the KIT mutation.19 Patients with the level between 15 and 25 ng/ml and a REMA score of 2 or higher or with the KIT D816V mutation detected in peripheral blood should also undergo bone marrow studies.18

The elevated tryptase level may be related to other comorbidities, including hematologic, nonhematologic reactive, and other disorders.2 Hematologic diseases include chronic leukemia (myeloid, eosinophilic, basophilic), acute basophilic or myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm especially with mutated PDGFR or FGFR genes, and myelomastocytic leukemia.2,29 Nonhematologic reactive conditions with elevated tryptase levels are allergic disorders, mainly exacerbated chronic urticaria, chronic inflammatory diseases, and chronic helminth infection. Other conditions include end-stage kidney disease and hereditary alpha tryptasemia. Elevated tryptase level can be rarely found in healthy individuals or as a false positive result due to heterophilic antibodies.2 Additional mediators, such as histamine in plasma or urine, histamine metabolites in urine, or prostaglandin metabolites in 24-hour urine collection, may also be used as indicators of MCA.30 The positive result should be based on an event-related increase in at least 2 of these mediators or, preferably, at least 50% higher values after the reaction in comparison with the baseline value.2